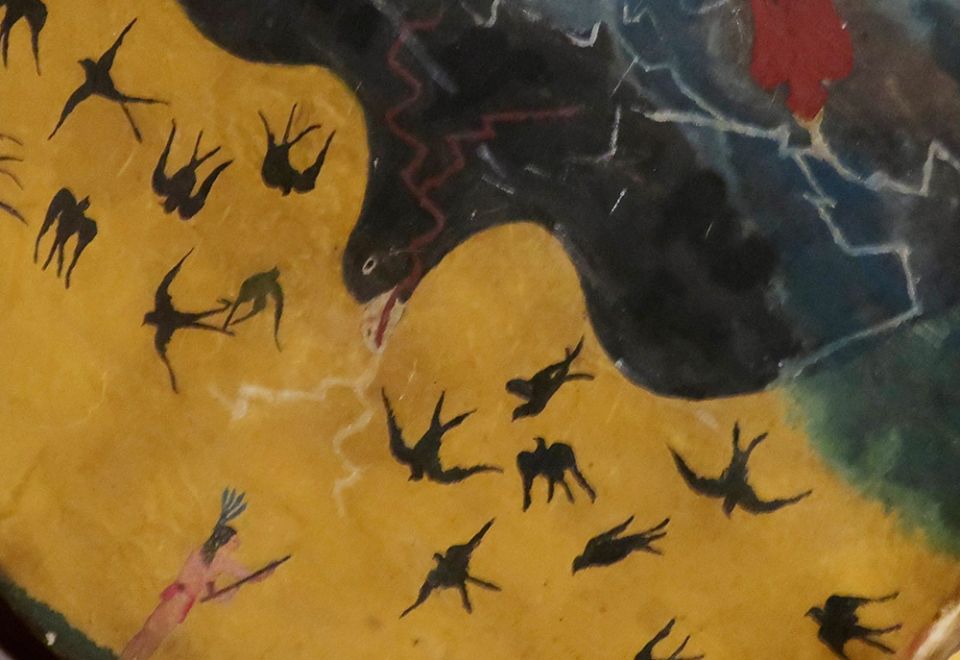

Ghost_Dance_Drum_by_George_Beaver,_Fenimore_Art_Museum CROP DETAIL.jpg

Christian salvation narratives often focus exclusively on Jesus' relationship with humanity, but Servant of God Nicholas Black Elk and the Ghost Dance tradition proclaim a broader vision of salvation: Jesus, "He Who Makes Live," is the whole Earth's greatest hope.

Many critics of Christianity draw a direct connection between Christian tradition and ecological degradation, such as Lynn White in his influential 1967 article "The Historical Roots of Our Ecological Crisis." For White, Christianity introduced the idea that humanity is not part of creation but above it, justifying exploitation of the Earth.

Many Christians have interpreted the message that way, but I think they and White have it backward. From the perspective of the Earth, God's incarnation and human yearning for God among us is not a cause of ecological collapse but a response to it. Therefore, Christian faith is actually the most relevant spirituality for our haunting ecological context, and this is well-illustrated by Indigenous engagement in Christianity through the Ghost Dance.

The Ghost Dance started with Wovoka, or "Wood Cutter" (circa 1856-1932), a Paiute from what colonists turned into Nevada. While in a coma, Wovoka traveled to Heaven in a vision during a solar eclipse on Jan. 1, 1889. There he met an Indigenous Christ and saw the New Heaven and New Earth promised in the Book of Revelation — the dead would rise and the land be healed of wounds inflicted by the newcomers. The only thing to do was live in peace, go to church and dance a new dance.

Wovoka's message of cosmic healing by the Messiah exploded across the Rocky Mountains into the plains as new Ghost Dance communities formed on reservations and reserves. Groups abstained from food and water, dancing all day in a circle around a tree symbol for the Indigenous Christ Wovoka had met, whom the Lakota called Waníkiya, "He Who Makes Live."

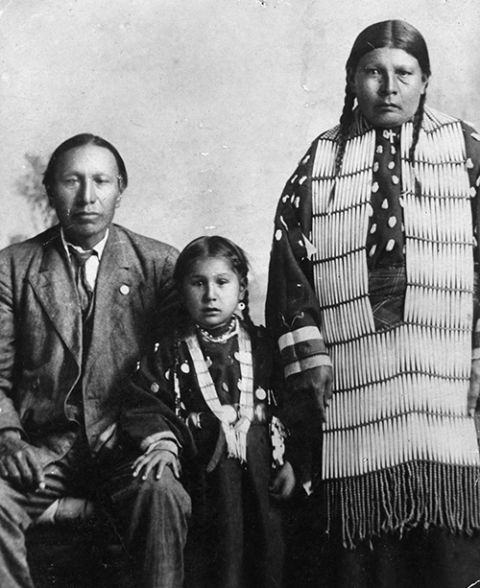

Nicholas Black Elk and family.jpg

Christ visited his children through numerous visions, the most famous being that of Black Elk, the Lakota holy man and candidate for sainthood in the Catholic Church. While dancing in 1890, he collapsed and had the last major vision of his life. Black Elk flew over the Promised Land and saw a man with an eagle feather in his long hair, pierced feet and hands and surrounded by light.

"My life is such that all earthly beings that grow belong to me," he told Black Elk. "My father has said this. You must say this."

This is a remarkable spiritual shift. Traditionally, Lakota spirituality was based on the cultivation of harmony, restoring imbalances within the cosmos and power to flourish within it. The Lakota didn't envision a Messiah to initiate a New Heaven and New Earth, but rather focused on spiritual relationships that maintained the world as it is, illustrated by the traditional Lakota prayer, "Be merciful that my people may live."

The Lakota spiritual emphasis on the principle of harmony mirrored its hunter-gatherer economy. Buffalo, wild turnips and other wild foods exist independently of humans. The way to maximize yield is by good management. As much as possible, you want the world to stay the same.

In the bestselling book Braiding Sweetgrass, Robin Wall Kimmerer calls this general Indigenous value a "moral covenant of reciprocity,' which leads to the flourishing of both humans and other-than-humans, where "people and land are good medicine for each other."

Contrast this perspective with that of agricultural societies. Growing food entails transforming the land, reducing biodiversity and cultivating a few highly productive species. Maximizing yield is based on expanding the amount of land under cultivation. Agriculture affords higher populations, which reinforces the need for more land.

Advertisement

Advertisement

But large and growing systems based on a limited number of species are much more susceptible to disruption from climate, such as droughts, floods or extreme temperatures. Higher populations make for larger-scale conflict. There is the real risk of collapse through famine and invasion.

The history of Israel exemplifies this cycle of collapse. While they maintained the spirituality of harmony — they called it Shalom — in this context the hope of a Messiah was born, adding a new principle of salvation, a power bigger than the entire cosmos that heals it of its brokenness.

In the 1800s, the Lakota and other nations faced collapse through invasion by an expanding agricultural society. The old ceremonies didn't address this. A new Spirit appeared and granted new power through new ceremonies.

Though unquestionably Indigenous in form, the Ghost Dance was at its core a literal reading of the Book of Revelation, which tells the story of a God who will "destroy those who destroy the earth" (Revelation 11:18), and an incorporation of the principle of salvation into traditional Lakota spirituality. Where traditional Lakota spirituality prayed, "Be merciful that my people may live," Waníkiya added, "Be merciful that my people may live again."

That the Ghost Dance was an organic, grass-roots movement highlights the importance of its function. The message was not introduced or controlled by foreign missionaries. The Ghost Dance flourished because Indigenous peoples believed that it directly addressed colonial problems while renewing Indigenous lifeways in a new context. Ghost Dancers forged a committed ceremonial life with a shared vision of God's action in all creation but embodied it within a tangible daily life in community.

Ghost_Dance_Drum_by_George_Beaver,_Fenimore_Art_Museum CROP VERT.jpg

This included participating in "mainstream" Christianity. Large numbers of Ghost Dancers entered conventional denominations because it was a tenet of the movement and because Waníkiya was the word used for savior in these traditions.

Black Elk became a prominent Catholic lay leader and carried on the Indigenous vision of the New Heaven and Earth. In July 1909, Black Elk wrote a letter in the Lakota Catholic newspaper assuring his fellow Lakota, "We all suffer in this land. ... But let me tell you, God has a special place for us when our time has come."

A materialist critic would make the important observation that this is a rather convenient imperialist package, a self-serving system of destruction containing its own opiate. It's also important to recognize that Black Elk and Indigenous peoples who engaged the Ghost Dance were not materialists; the Spirits are real and their power is essential for living in this world.

From this perspective, Christian salvation is not so much a cause of collapse as an authentic spiritual response to a tragic human tendency that magnifies as our societies grow, a kind of medicine given by the Spirits. And if you don't respond to the Spirits with the ceremonies they give you, the people will become weak and won't be able to face the storms that exist regardless of what we think are their causes.

Seen through the lens of the Ghost Dance, Christian faith is actually the most relevant spirituality for our haunting ecological context — one that integrates the best of our human heritage, both the principles of harmony and salvation, exemplified by Black Elk. He knew the sacredness of the Earth, whom he called in The Sacred Pipe "the only mother that has shown mercy to her children," and lived the hope of Christ, who called him to share the message that "all earthly beings that grow belong to me."

Black Elk and the Ghost Dance should be an inspiration for us to have new confidence in God's restorative action as we seek to renew our spiritual inheritance, recover ancestral traditions and build not only a sustainable future but one based on mutually sustaining reciprocity with all the beings that surround us.

God be merciful, that we may live and live again.