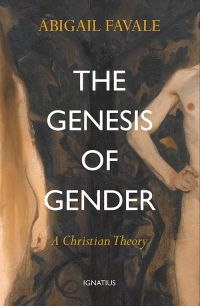

Everyone in 2022 America has an opinion on transgender issues; news outlets with incendiary headlines have made sure of that. Enter Abigail Favale, professor at the University of Notre Dame's McGrath Institute for Church Life, with the June 2022 release of her book The Genesis of Gender: A Christian Theory from Ignatius Press.

The book promises "an intellectually honest, respectful, and faithfully Catholic view" tracing the philosophical origin of gender studies through a distinctly academic Christian feminist lens. Yet it leaves out quite a bit of the story.

Writing in a matter-of-fact rhetorical style, Favale highlights philosophers and writers that either prove her point or provoke outrage while sprinkling in personal anecdotes and stories from detransitioners (while trotting out scientific studies that play to one side), to ultimately make the claim that she has fully and fairly vetted the field of gender studies — and found it wanting.

Reading the book as a transgender man, I must say none of the theories, information or scientific studies sketched out in the book surprised me; after all, I've been on the internet long enough to see many theories come and go. But I was disappointed to see that Favale purposefully laid a breadcrumb trail of implications that would lead any innocent reader to a conspiratorial conclusion involving modern feminists, politics and "big pharma."

Advertisement

Advertisement

She creates a boogeyman called the "gender paradigm," a phrase she uses to refer to the increased visibility of the transgender and genderqueer community in modern social and legal discourse. (In Favale's mind, this increase of visibility is negative.) She intends for us to believe the goal of this gender paradigm is social and individual destruction — and that it is succeeding.

The Genesis of Gender is a book full of "$10 words," as Favale calls them, and contradictory statements that are not intended to come together into a coherent defense of what she believes. Rather, they are designed as a shotgun-style attack against not only the identity of transgender and genderqueer people themselves but also against any philosophical or intellectual thought on the topic of gender that doesn't follow a strict binary of male/female or appeal to Favale's worldview. Her strategy hinges on firing off so many shots that the reader will be unable to follow the thread of her argument closely enough to ask questions or defend the concepts she's attacking.

There is not enough conviction in the book to make any singularly important point and the Genesis story might as well be a footnote for as much as it is referenced. (Speaking of footnotes, the first one directs the reader to Favale's own book.)

The author claims to feel called to make a defense of what it means to be a woman, yet conveniently casts herself in the nonconforming stereotype she seeks to ridicule as farce (she mentions having "more body hair than the platonic ideal" several times), and never paints a picture to which women should aspire.

Because she does not submit her own definition of woman, Favale leaves the reader hanging. The profound experience of human embodiment is less interesting to Favale than creating a villain to attack.

Favale's concern for defining womanhood feels more like a search for a weapon to level at trans women, whom she implies are all secretly predatory men, than an actual search for truth. Favale fails to give any definition that would echo the poetic archetype in the story of the first man and the first woman in the Garden of Eden.

Growing up Catholic, I loved the beauty of the Mass, receiving the sacraments and participating in the wonderful patchwork community of people from all walks of life. In my younger years, I read all the individual theories that Favale brings together in her book and never felt satisfied by what I found.

The struggle of my own transgender life was not in identifying myself or in knowing who I was, but in realizing that those who told me they loved me would only respect me if I played a role that did not ring true to me. I found myself in the position of losing my Catholic family's love and support at a critical time in my life.

When I medically transitioned at 29 years old, I wanted my mom and my dad to be there with me at my doctor's appointments. I wanted them to be waiting to pick me up after surgery, to take me home and feed me soup and put on my favorite movies while I rested, recovered and ultimately celebrated the miracle of releasing the gender dysphoria that had plagued me for decades. I wanted my parents to use my name and pronouns and to celebrate me as their son.

Favale would see their refusal to do so as the loving act, but I have instead experienced the profound loss of parental support when it was most needed. They have been cold and distant to me ever since I shared who I am with them, preferring dogmatic legalism over willingness to see the real me, who is still their child.

Favale talks about the body from a view that transgender identities reject the truths contained within the body. Her thesis is "the body reveals the person." This is undoubtedly true, but a further understanding of the body requires us to acknowledge that the person animates the body.

It is the person who, over their lifetime, smiles and laughs or yells and frowns to the extent that physical wrinkles are left upon their body when they die. We may be born with dewy soft skin, but few of us are privileged enough to make it to the end of our lives without a few scars. Christ himself bears witness to this, allowing the marks of his death to remain visible on his heavenly body in the Resurrection.

Favale references the powerful image of the crucifixion, but does not see the connection between the scars of Christ and the scars of a transgender person — she doesn't make the final connection between Genesis and Calvary. The mystery of the Incarnation, Crucifixion and Resurrection are not just the source of human redemption but also a profound meditation on the experience of human embodiment.

Even though I lost my parent's support when I transitioned, there are still Catholics who support me. In a world preoccupied with verifying or vilifying the experience of being trans, there are still Catholics who love me without question. Without deliberating over my name and pronouns. Catholics from all walks of life have made a seamless transition from using my old name to my new one, Catholics like my 73-year-old Aunt Dorothy, who wrote me a Christmas card the year I came out that said, "I am happy to have another nephew," Catholics for whom I am not a theological problem to be solved but a transgender person to be loved.